Abstract

As a robust, accessible, and affordable resource, the internet became the primary information means. This includes sensitive and stigmatized- health-related topics, where user’s privacy is considered advantageous. However, its free dissemination makes it difficult to distinguish true information. The recent “infodemic” highlighted the info-literacy problem through the widespread of false COVID-19-related e-information rather than the evidence-based ones.

To investigate the factors that may influence people’s credibility in evaluating e-sources, we conducted this study where 596 Arabic-speaking participants from different countries participated in an online test that examined the participants’ ability to differentiate reliable sources. statements and screen-shots of their source pages were presented and participants were asked to classify them according to their accuracy and their sources’reliability.

Results showed statistically significant differences for: country of birth, country of residence, level of English language, educational qualifications, field of

study, and professional orientation (P< 0.05). Using multivariate analysis; country of residency was the most effective factor (P˂0.001). Additional effective factors with statistically significant differences were: professional orientation and field of study. The study suggests that national educational programs must match this development and teach students reliable sources’ types and how to verify the validity of the e-information.

Introduction

Internet information consumption has exponentially increased in the past years, along with a simultaneous increase in available web resources of various credibility levels. Considering the increasing Internet reliance during the current COVID-19 pandemic, it became an urgent need to understand users’ ability to evaluate the credibility of online-based information(1). Additionally, research has shown that a large amount of information is spreading on the web regarding COVID-19, where the biggest portion of shared information is false rather than evidence-based. This led the World Health Organization (WHO) to name the situation at hand as an “infodemic”(2-3); which is defined as an accelerated spread of diverse information regarding a problem and thereby impeding the solution(4-5). A similar situation was exhibited during the SARS outbreak, as the virus remained in the top 20 internet searches for two months. The demand for health-related information has grown (4.5% of all searches on the web), leading to what we now know to be an “infodemic” (6). With the rise of technology and internet use, a significant part of the information

shared on the internet is false or inaccurate. This poses infodemic as an uprising challenge.

False information includes any inaccurate or misleading information including fabrication, hearsay, hoaxes, and conspiracy theories shared on the web deliberately or accidentally. As pointed out in a report released by the World Economic Form in 2013(7), fake news is one of the main threats of our current society(3).

Online information reliance and insufficient search skills are not only exclusive to laypeople but also extend to students and professionals. Research suggests that students are increasingly using the web

for educational and social purposes, thus, they may come across the problem of conflicting knowledge claims from various resources of different qualifications. The leading cause for this problem is the lack of editorial control over information spread online(8).

This reliance can be due to a great increase in the quantity and quality of internet information. Additionally, information has become more accessible, affordable, and widely available(9). User privacy is another advantage that allows them to search for sensitive health and mental health topics in private as many of these topics are heavily stigmatized in societies(6).

Despite of all these advantages of using the Internet as one of the main information resources, this reliance has several disadvantages. Internet access allows users to freely share information online, rendering its accuracy very limited(10-11). When combined with limited search skills of users, this could posit a serious issue, as online health information seekers are apt to use less complex terminology when searching on the web, frequently misspelling the search words(12-15). Moreover, the majority of users limit themselves to the first two pages of citations found on the web(6-20) on the other hand, most health education materials found online and offline are higher than the average readability level as suggested by the US national institutes of health(21-27).

The downsides of online information reliance can be minimized by obtaining information from credible online sources only. Credibility is defined as the believability of information and its source(28), which possesses two main factors: expertise and trustworthiness, and secondary factors that include

attractiveness and dynamism(29-30). Many concerns regarding internet health information credibility were raised in a review(19), which found that over 70% of studies investigatingquality of online health resources reported problems with source quality and use(6). Moreover, users also vary in their eligibility to evaluate information resources quality and credibility 31.

Many reasons can be attributed to user’s inability to evaluate and filter information successfully(32) including neglect to educate users on information literacy (32) and users failing to remember to check the web page for indicators of credibility (18).

Additionally, users’s eligibility to evaluate the quality of Internet information is influenced by several factors; content-related and individual-related. A study, identifying content-related criteria that users adopt to evaluate the information, found that the most often reported criteria are trustworthiness, expertise, and objectivity. Less frequently identified criteria are transparency, popularity, and understandability. Eight other criteria including relevance, familiarity, accessibility, identification, believability, accuracy, readability, and currency were reported in some other articles (33).

On the other hand, individual-related factors have a substantial impact on users’ eligibility to evaluate the quality of online information. When evaluating demographic factors such as gender (34-43) education (34-45), health status (34-48), and income regarding time spent online and trust of online information, a number of conflicting findings have been established(49). No conclusive answers have been drawn as to whether any of these factors directly affects the internet use and information trust (49) .

Methods

A quiz-like questionnaire was created using Google Forms®, which later on was completed by (596) participants.

Participants were enrolled unconditionally, except for age which was the only controlled criterion (>=18 years). The main purpose of the questionnaire was to examine the participants’ ability to distinguish between reliable and unreliable sources. The questionnaire was applied on an online network; conducted on Facebook® and Instagram® using many platforms as described before (50) . It was available to participate for two months ( launched on July 1st, 2019 and closed on September 1st, 2019).

The questionnaire was launched after testing it on different types of browsers including Google

Chrome®, Safari®, and Mozilla Firefox®. Moreover, it has been tested on various types of operating systems including Android®, IOS®, and Windows®. To validate the questionnaire and to estimate the time required to complete it, the questionnaire was completed and experienced by a group of eight volunteers, who took an average of 7-10 minutes to complete. Feedback was used to adapt the survey.

No participants were allowed to complete the questionnaire unless they expressed their consent. Participants approved their acceptance after reading the informed consent sheet on the first page of the questionnaire. Their participation was voluntary and anonymous along the way.

Withdrawal from the study was allowed at any point. Quitting the questionnaire was considered as a withdrawal. Nine respondents had withdrawn; thus, the final number of participants was 587.

Study Tools

On the second page of the questionnaire and before taking it, the participants were asked to select their gender (male or female), their country of birth, country of residency, level of education (elementary school, middle school, high school, undergraduate, graduate, Master’s or Ph.D.), and what is their field of study (scientific, literary, commercial or industrial), along with specifying their professional orientation (medical, geometric, business, technology, teaching or artistic field) and their level of English (beginner, intermediate or advanced).

on the third page while introducing the questionnaire, the following two expressions were explained; the true statement and the trustworthy source. The target population was Arabic language speakers aged 18 years or more.

Sixteen multiple-choice questions needed to be answered; each question is a statement that should be classified as one of 5 choices which are: (true statement from a reliable source, true statement from an unreliable source, false statement from a reliable source, false statement from an unreliable source, I don’t know). The four questionnaire subjects were chosen from four different fields; each one consistsof four paragraphs to cover four different topics.

The first subject was medical topics (which included the following: managing bleeding, best first aid position for fainting, fingers cracking, and hair

growth). The second subject was biology (which included the following topics: arterial physiology, photosynthesis, the effect of green tea on the level of iron in the body, and the crocodile’s behavior to stay underwater). The third subject was the environment (which included the following topics: the physical state of the lakes, E-wastes, global warming, and plastic bags). The fourth group of questions was of miscellaneous topics: The Mona-Lisa® painting’s site, the benefits of coffee for soil, the synonyms of the word “love” in Arabic, and the reality of pseudoscience.

An image of the source page, from which the statement was extracted, was attached to the question field of each statement, as well as the source link.

All used sources were in English. Eight statements out of sixteen were translated and written in Arabic while the other eight were in English; to end up with two Arabic paragraphs and two English paragraphs in each subject of the four questionnaire subjects. The questionnaire result was shown after submission. No duplicate form was accepted

Data processing and statistical analysis

Data processing

The data set was password protected.

Each participant was given a unique identification number.

Answers were given numerical values using two methods of evaluation, one at a time:

1- Integrative approach:

In which the points were given as follows:

2- Differential points:

In which the points were given as follows:

One point (1) for each correct answer.

Zero points (0) for each half-correct answer.

Zero points (0) for each wrong answer.

By half-correct answer, we mean that the participant has incorrectly evaluated the information or source.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis for the processed Data was performed using SPSS® version 20 (IBM) for General Linear Model (Multivariate) and Independent Sample t-Test.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

A total of 587 responses were included: 338 (57.58%) of the respondents were male and 249 (42.42%) were female. All participants were over 18 years old; 296 (50.42%) were ≤ 22 years old, while 291 (49.57%) were > 22 years old.

491 (83.64%) of the respondents were born in Syria and 96 (16.35%) were born in Arab or foreign countries. A total of 412 (70.19%) of the respondents were residing in Syria at the time of participation and 175 (29.81%) were residing in Arab or foreign countries. The education level was undergraduate, graduate, master’s, or doctorate (Ph.D) for 539 (91.82%) of the respondents while it was primary, middle, or high school for 48 (8.18%) of them. The field of education was scientific for 510 participants (86.88%) while it was literary, commercial, industrial, or other for 77 (13.12%) of them.

251 (42.76%) of the respondents declared that they have an advanced English language level whereas 336 (57.24%) declared having a beginner or intermediate level. The largest share was for medical, geometric, technology, or teaching careers, reaching 60.48% (355 respondents), while the percentage of those with a business, artistic field, or were unemployed was 39.52% (232), as summarized in (Table A1).

Independent factors assessment

As shown in Table A2, and by comparing the means of integrative points for each variable according to Independent Samples T-test; No statistically significant effect of gender and age was observed. In contrast, statistically significant differences were recorded for: country of birth, country of residence, level of English language, educational qualifications, field of study and professional orientation with a statistically significant difference and a P-value of (< 0.05).

On the other hand, a significant effect was observed for gender, country of residence, educational qualifications, level of English language, field of study, and professional orientation on the means of the differential points with a (P-value<0.05) for each of these variables. However, no significant effect for age and country of birth on the responses of the participants was observed.

Multivariate analysis

As shown in table A2, a model composed of: country of birth, country of residency, educational

qualifications, level of English language, field of study and, professional orientation; was used for Multivariate analysis.

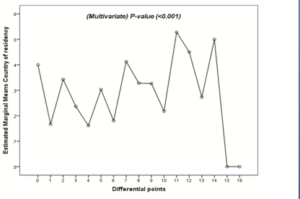

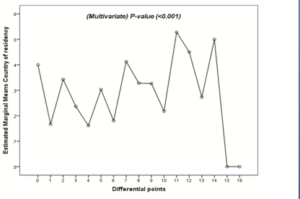

Using the differential method, country of residency was the most effective factor in the responses of the participants with a (Multivariate) test P-value (˂0.001) as shown as (Fig. B1).

Participants residing out of Syria scored significantly better points (7.17) than those in Syria (6.55) (Table A2).

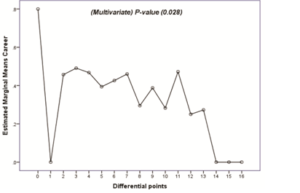

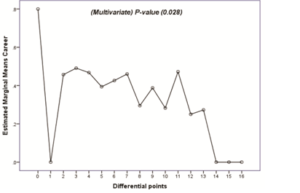

However professional orientation was also an effective factor with a statistically significant difference and a P-value =0.028 (Fig. B2).

The highest points scored by the participants working in medical, geometric, technology, or teaching (7.06) compared with workers in business, artistic field or unemployed (6.25) (Table A2).

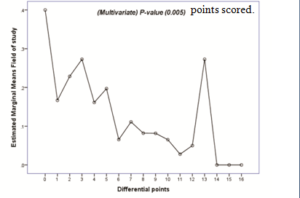

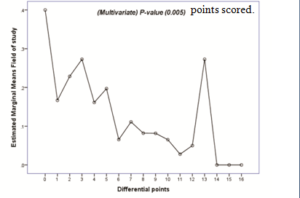

The responses of the participants were further influenced by the field of study as demonstrated through the use of both differential and integrative methods, with P-values of (0.005), (˂0.001) respectively as shown in (Fig. B3). Participants who study literary, commercial, industrial, or other fields scored lower points (5.30) than to whom with scientific majors (6.95) (Table A2).

No effects of these factors: gender, English language level, educational qualification, were recorded in this study on the participants’ responses in both differential or integral methods.

Discussion

Nowadays, individuals have access to potentially unlimited amounts of information on the internet. However, this accessibility is a double-edged sword that allows the dissemination of information regardless of its authenticity, and this requires recipients to have sufficient awareness in order to distinguish between reliable and unreliable online sources. This study aimed to investigate this awareness and the factors affecting it among Arabic speakers. Factors included in the analysis are gender, age, academic level, country of birth, country of residence, English language level, science/non-science majors, and career/professional orientation.

The data obtained from the online questionnaire was analyzed using T-Test and Multivariate Tests, and the results of the data analysis assert the importance of the field of study of the participants (scientific vs. other majors) in identifying the

(74) developed an educational unit that represents a set of activities designed to help students adopt a critical stance while conducting research online and with multiple sources, this training unit has produced a significant advantage in distinguishing between reliable and unreliable information among the undergraduates who received training in the University of Illinois at Chicago. It is also useful to teach students the basic principles of knowledge of scientific journals and peer-reviewed research papers as the most reliable online sources.

Conducting studies similar to this study in other countries with different languages and on a larger number of participants can be useful to assert the results of this study and to figure out the influences that cultural and social differences and digital development can have on the study findings; subsequent studies are also necessary to ensure data accuracy and generalizability.

Conclusion

This study suggests that educational curricula must keep pace with digital developments, allocate knowledge to students about the types of reliable sources, and how to verify the validity of the information they obtain on the network. Furthermore, studies from other countries to verify the applicability of these results and to test more factors influencing the selection of reliable sources are strongly recommended. The recent “infodemic” has spotlighted the problem of web-based information literacy.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

cultural context is pivotal (57), and this is relatively consistent with the results of our study, in which the country of residence and country of birth affected the results considerably, so participants who were born in Syria had less correct answers than those born abroad. Another highly possible explanation to this is the belated availability of affordable Internet connection in Syria , as in the year 2010, wired-broadband subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in Syria were limited to 0.3 58 making it difficult for users to familiarize themselves with the different sources on the network. However, we cannot ignore the

conclusion of a study (59) which indicates that abilities and performance related to Internet use can vary among subcultures not only due to the digital divide but also due to cultural dissimilarities.

Some studies found that there are cross-cultural differences patterns in the search for online health information (6-60). It is also worth mentioning that a study (61) concluded that the values of immigrants are highly expected to change after emigrating to a new country, and the relationship between the values of immigrants and the country of residence appeared to be higher than between them and the country of birth. It seems that we may be able adopt this result as an evidence of the influence of society and country of residence on the culture and preferences of individuals in order to explain our findings.

Since our study has also covered environmental and medical scientific information, we can consider the findings of (62) a study which investigated the influence of age (17-25, 26-40, >40) and educational level (Bs, MSc., and Ph.D) on environmental awareness; these findings revealed that the increase in age and education levels affects positively the environmental awareness and attitude. One study showed that younger people (25-55 years) trust online info less than older people(49-63), while one showed that they trust online info/go online more(35-44). This contrasts with the results of our study, as the educational level and the age factor had no obvious impact on the results. the explanation for the insignificant role of the age factor could be the predominance of the age group (18-25) by 76% of the participants in the questionnaire. However, the age factor had also an impact in (56) study which implied that elderly persons are less likely to consider internet health information sources as credible. On the other hand, in the same study (56),

References

Freeman, K. S. & Spyridakis, J. H. An Examination of Factors That Affect the Credibility of

Online Health Information. Society for Technical Communication 51, 239-263(25) (2004).

Acknowledgements:

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions:

Conceptualization and design: T.A. and W.A.

Data collection: W.A., M.R., M.J., A.M. and T.A.

Data analysis: W.A. and T.A.

All authors contributed to Bibliography, Drafting, Draft reviewing and editing.

Table 1. Characteristics of included respondents

| Variable | Strata | Percentage (%) and Number of Respondents |

| Gender | Male | 338 (57.58) |

| Female | 249 (42.42) | |

| Age | ≤ 22 | 296 (50.42) |

| > 22 | 291 (49.57) | |

| Country of Birth | Syria | 491 (83.64) |

| Arab or Foreign countries | 96 (16.35) | |

| Country of Residency | Syria | 412 (70.19) |

| Arab or Foreign countries | 175 (29.81) | |

| Educational Qualification | Undergraduate, Graduate, Master’s or Ph.D. | 539 (91.82) |

| Elementary, Middle or High School | 48 (8.18) | |

| Field of Study | Scientific | 510 (86.88) |

| Literary, Commercial, Industrial or Other. | 77 (13.12) | |

| English Level | Advanced | 251 (42.76) |

| Beginner or Intermediate | 336 (57.24) | |

| Professional Orientation | Medical, Geometric, Technology or Teaching | 355 (60.48) |

| Business, Artistic field or Unemployed | 232 (39.52) |

Figure B1. Country of residency was the most effective factor in the responses of the participants using the differential method for mean points scored.

Figure B2. Professional orientation was an effective factor in the responses of the participants, using the differential method for mean points scored.

Figure B3. Field of study was an effective factor in the responses of the participants, using the differential method for mean points scored.

Table 2. Results of univariate analysis for both integrative and differentiative methods. The table also shows the model-composing factors chosen for the Multivariate model analysis (with gray highlights).

| Variable | Strata | Independent Samples T_ Test | |||||||

| Integrative Points | Differential Point | ||||||||

| Mean | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | Mean | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | ||

| Gender | Male | 18.97 | .162 | .622 | .444 | 6.94 | .074 | .476 | .265 |

| Female | 18.35 | 6.46 | |||||||

| Age | ≤ 22 | 18.61 | .661 | -.193- | .440 | 6.57 | .202 | -.333- | .260 |

| > 22 | 18.80 | 6.90 | |||||||

| Country of Birth | Syria | 18.50 | .035 | -1.251- | .587 | 6.65 | .127 | -.552- | .360 |

| Arab or Foreign countries | 19.75 | 7.20 | |||||||

| Country of Residency | Syria | 18.34 | .010 | -1.228- | .475 | 6.55 | .033 | -.612- | .286 |

| Arab or Foreign countries | 19.57 | 7.17 | |||||||

| Educational Qualification | Undergraduate, Graduate, Master’s or Ph.D | 18.93 | .000 | -2.740- | .718 | 6.85 | .001 | -1.437- | .403 |

| Elementary, Middle or High School | 16.19 | 5.42 | |||||||

| Field of Study | Scientific | 19.09 | .000 | 2.947 | .695 | 6.95 | .000 | 1.654 | .371 |

| Literary, Commercial, Industrial or Other | 16.14 | 5.30 | |||||||

| level of English language | Advanced | 20.33 | .000 | -2.850- | .428 | 7.63 | .000 | -1.568- | .255 |

| Beginner or Intermediate | 17.49 | 6.07 | |||||||

| Professional Orientation | Medical, Geometric, Technology or Teaching | 19.18 | .006 | 1.206 | .440 | 7.06 | .002 | .811 | .259 |

| Business, Artistic field or Unemployed | 17.97 | 6.25 | |||||||

Keywords: Coronavirus; COVID-19; E-Resource; Infodemic; Credibility.

Corresponding author:

*Walaa. Abdul Rahman, Faculty of Medicine, Damascus University, Damascus, Syria

Email address: massajabra@gmail.com

Funding

The authors received no financial support for their research, participation and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest